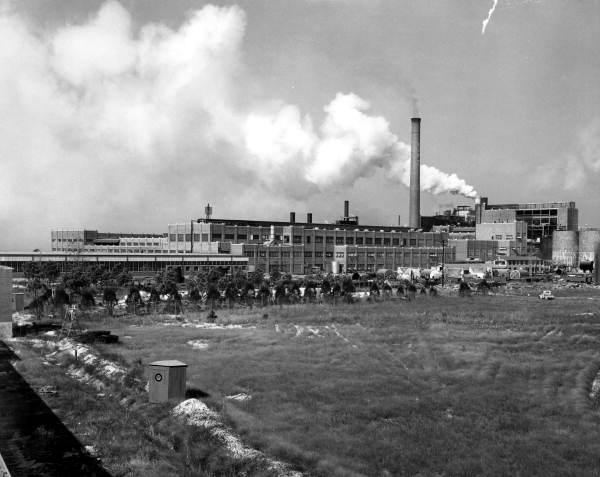

Hidden in Florida’s forgotten coast, a two-lane road weaves between long-leaf pines to the town of Port St Joe. When crossing the absurdly steep bridge over the intercoastal, you can see a large empty plot of dirt and concrete, the site of a former monolithic paper mill.

The Port St. Joe Health Equity Transformative Scenarios Workshop took place between Feb. 22-24, 2024. Dr. Kwame Owusu-Daaku, a qualitative geoscientist and professor at the University of West Florida, led the workshop with support from Dr. Christian Wells, a mixed-methods anthropologist, and professor at the University of South Florida. They coordinated with residents to discuss the future they want to see in their community, one which is haunted by its industrial past.

Between logging, shipbuilding, a chemical plant, and a papermill, the town was once a powerhouse of production. Over the years, the sites quietly shut down. The former St Joe Paper Company’s forest products site closed in 1998 due to financial difficulties after ownership was exchanged between several other companies. Later in 2009, the Arizona Chemical plant shut down, moving its operations to refineries in Panama City, Florida, and Savannah, Georgia.

Gulf County was devastated, with some sources saying unemployment soared to 20%. While the jobs were missed, the paper mill’s absence brought the many issues it caused to the community to light.

Gulf County was devastated, with some sources saying unemployment soared to 20%. While the jobs were missed, the paper mill’s absence brought the many issues it caused to the community to light.

Many homes in the north Port St Joe community, a historic and currently black community, are sinking into the ground. The roofs and foundations are cracking and shifting as they descend into the topsoil. They were built on the old dumping site of the mill. Soil samples from the DEP found arsenic, PCBs, vanadium and lead.

In 2002, homeowners and community residents protested the St Joe Company, (the former mill operator,) who sold them the land the houses were built on. At the time, the Senior Vice President of external affairs blamed the homebuilders and claimed shoddy construction. One local quipped back that the driveways were cracking at 45-degree angles.

In 2007, a claim for environmental discrimination on behalf of the residents of North Port St Joe revealed that the neighborhood was the only place where banks would give home loans to black residents, a phenomenon known as redlining.

The claim by Carolyn Chapman, at the time the director of the office for civil rights at the Environmental Protection Agency, says “For decades, the St Joe Company, with the knowledge and acquiescence of the City of Port St Joe, dumped toxic waste in the area. The St Joe Company then sold the land to their black workers for housing.”

She goes on to describe some of the ways the city of Port St Joe intentionally disinvested in the NPSJ neighborhood over the years. Chapman also claims that the city made deals with the St Joe Company to sell off a marina while making the neighborhood a target of eminent domain through a revitalization program.

She goes on to describe some of the ways the city of Port St Joe intentionally disinvested in the NPSJ neighborhood over the years. Chapman also claims that the city made deals with the St Joe Company to sell off a marina while making the neighborhood a target of eminent domain through a revitalization program.

The situation worsened for the NPSJ neighborhood after Hurricane Michael in 2018, a category five storm that decimated Northwest Florida. Homes were destroyed, decreasing the already sparse amount of affordable housing, and others fell into disrepair. For many, aid was delayed or never seen.

Two years later, the COVID-19 pandemic began, which only worsened economic outcomes for the area.

North Port St Joe, unfortunately to the residents who envision a different future, is a prime location for industrial development. It has direct access to an intercoastal waterway, train tracks, a deepwater seaport, relatively cheap land, and a local government that would most likely be more than accommodating.

Locals recently won a fight against a liquid natural gas facility that was set to be constructed in their neighborhood. At the transformative workshop, participants mentioned that the community wasn’t notified that it was going to be constructed in their backyard. Public Citizen, a think tank out of Washington D.C. reached out to locals about the project before there was any announcement.

The land owned by the St Joe Company was intended to be developed by the Liquid Natural Gas Company Nopetro. Several hundred Port St. Joe residents attended community meetings where they voiced their opposition to the plant. A lawsuit by Public Citizen and considerable community pushback led to the project being canceled.

Industrial development, pollution, a legacy of racism, and a legacy of what many perceive as a “good ole boy” system in local governments, are just a handful of the threats to North Port St Joe. Displacement is one of the most existential contenders brought up at the transformative workshop.

The St Joe Company’s shift towards luxury development and their massive land holdings in Northwest Florida exaggerate the existing housing crisis in the state. Redevelopment and new luxury constructions drive up property values and as a result, rent in areas where they are built. The average price of a home in Port St Joe increased 7.4% over the last year with a $458 thousand price tag. That probably doesn’t seem that expensive compared to other Florida cities but in a relatively isolated and small community that can be a big deal.

As rent and property values go up with surrounding development, some locals worry about being priced out. With few to no protections in place for the people living there, this could lead to gentrification and simply displace the community.

At the workshop, Dannie Bolden, a long-time resident and community organizer, brought up how the area didn’t always look like this. Martin Luther King Boulevard, the main road running through North Port St Joe and connecting it to downtown Port St Joe, used to be thriving with many locally owned businesses. Years of insufficient support, neglect, and the closing of industry led to a decline.

According to the attendees at the transformative workshop, the local government hasn’t been at all supportive of their efforts to preserve and improve the neighborhood. This makes it difficult to actualize the future the community has envisioned for themselves. They would like to move away from heavy industry and into the tourism market in a way that doesn’t displace local residents. There were mentions at the event that redeveloping the old mill site into an outdoor commercial space was proposed before, and that they would much rather see a similar use of the space in that regard as opposed to more industry.

Some locals could attest to corruption taking place up to the legislative level. Bolden claimed he is on a texting basis with a local representative who has a sometimes adversarial relationship with their North Port St Joe Project Area Coalition. A look through Open Secrets appears to show that companies and interest groups in Northwest Florida contribute considerably to specific local representatives.

A consensus of members at the workshop was that they would like to begin community health monitoring to discover the long-term effects of the pollution from the former industrial sites. In their breakout groups, they identified disparities in Port St Joe and ideas on how to start resolving them. Their approach to health was a holistic community concept in regards to things as simple as access to fresh food could influence health outcomes. Due to the legacies of redlining and pollution in the area, these outcomes could be influenced by racism.

The Leadership, Empowerment, and Authentic Development (LEAD) Coalition of Bay County hosted the transformative scenarios team and showcased how they’re dealing with issues in the Panama City area. LEAD provided a tour of the Callaway, Springfield, and Parker areas and highlighted how problems Port St Joe is facing are similar to those of other post-industrial communities in Northwest Florida.

The Leadership, Empowerment, and Authentic Development (LEAD) Coalition of Bay County hosted the transformative scenarios team and showcased how they’re dealing with issues in the Panama City area. LEAD provided a tour of the Callaway, Springfield, and Parker areas and highlighted how problems Port St Joe is facing are similar to those of other post-industrial communities in Northwest Florida.

Disinvestment, housing attainment, blight, food deserts, a lack of career opportunities for young people, and a plethora of other issues face both communities.

While community members in Port St Joe face an uphill battle in the fight for North Port St Joe, they continue to reach milestones in envisioning a better future. Dayna Reggero, a documentary filmmaker, worked with Bolden to organize the community’s first Earth Day, which will take place this April.