Is Florida full?

A common sentiment amongst Florida residents online and on social media is that the state is full. Especially in the state’s southern peninsula, an influx of new residents to the urban expanse is straining roadways and shopping centers. One struggling to find parking in any downtown Florida city may share this belief with the online denizens of Sunshine State.

To get to the root of this question, let’s break down the idea of full by several categories:

Population influx

In 2022, Florida was the fastest-growing state in the union. Since 2010 the state has grown by 1.4%, adding 3.4 million people.

“Our estimates suggest that over the next five years, our population will grow by almost 300,000 new residents per year, over 800 per day,” Senate President Kathleen Passidomo said in a memo to Florida State Senators. “That is like adding a city slightly smaller than Orlando, but larger than St. Petersburg every year.”

Miami Realtors pushed out a statistic that same year, 2022, that Florida had the highest net migration in the country, just behind Texas.

These new residents are largely coming from New York, California and New Jersey according to Miami Realtors. The surge of baby boomers entering retirement is a large driver of this, with the largest new population demographic being between 60-69. The second-largest demographic moving into the state is between 50-59.

Cost of living

Cost of living

In a place constrained on all sides by water, the population surge has some downstream effects. The median home price was $404 thousand, a 5.2% year-over-year increase over the past five years. However, this isn’t far off from the national average of $403 thousand. The real issue with the housing prices for the working population is that the state hasn’t seen any significant wage growth to match the rising costs.

At the same time that the price of buying a home increased, Median Household incomes in Florida between 2018 and 2022 only rose from $63,160 in 2018 to $65,370 in 2022. This might partially contribute to the outflow of some Florida metropolitan areas. 275,266 people left the state as a whole, and other cities shrank. The population of the Miami Fort-Lauderdale metropolitan area decreased by 1,262 residents.

The sheer size of Florida, a whopping 65,758 square miles, means that the cost of living situation is going to vary greatly depending on where you go. According to RentCafe, places like Miami and Fort Lauderdale sit at a cost of living over 20% higher than the national average. On the flip side, cities like Pensacola or Tallahassee have a 6% lower cost of living than the national average.

To give an economic explanation for the lower cost of living, let’s look at Pensacola. The Pensacola metropolitan area, between 2018 and 2022, added 27,716 residents. The median listing price of a home rose from $250 thousand to $369 thousand. In December of 2022, there were 25,053 listed residential units for sale or rent. The area added a significant number of housing units for the incoming population, which led to less of a price hike than neighbors in higher-cost areas.

For the higher cost of living in the south end of the state, let’s look at the Miami-Fort Lauderdale metropolitan area. Listed units for rent and sale decreased by $21,053 at the same time as their population shrank. The price of a listed unit increased from $389 thousand to $595 thousand in the same period.

The state of Florida at large listed 43,539 fewer units for sale or rent in 2022 than it did in 2018. This is despite the massive population influx that occurred at the same time.

While not included in the data on the price of a home, a major issue that’s been highlighted time and time again in the actual price of home ownership in the state is home insurance. However readers might want to interpret this issue, whether it’s climate change, causing more and stronger storms or a complicated political battle, it’s still increasing year after year.

According to the Insurance Information Institute, homeowner’s insurance has increased 102% in the last three years in Florida and costs three times more than the national average. The average cost of home insurance in the Sunshine State in 2023 was about $6,000, the highest average premium in the U.S.

The strain on the environment

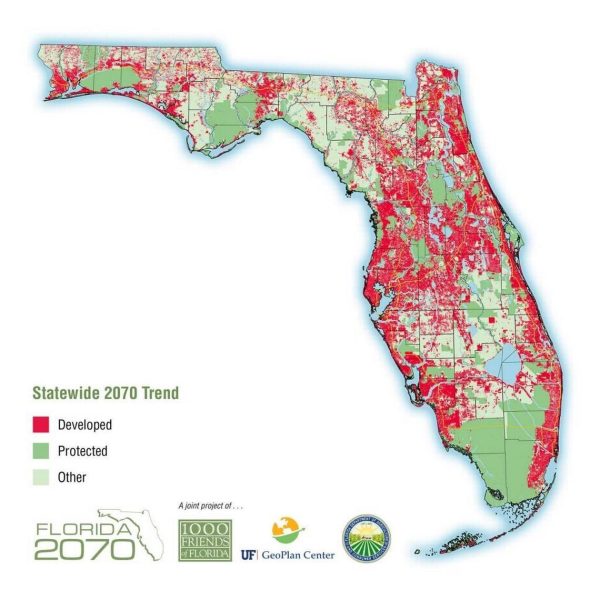

According to a study released by the University of Florida and 1000 Friends of Florida, about 1 million more undeveloped acres could be paved over in less than two decades.

15% of the state, or 5.4 million acres, are already developed. If existing development patterns persist over the next 17 years, that amount could expand to 18%. Many of the areas predicted to avoid development, mostly wetlands and other areas already protected, are expected to be lost to sea level rise. 206,000 acres targeted for the Florida Wildlife Corridor could be lost to similar development patterns.

“There’s no plan of action, there’s no holistic view of how we protect our water and land resources,” said Lee Constantine, a Seminole County commissioner and former GOP state senator who has been a leader on environmental issues. His views have been echoed by several critics on state policy surrounding land use and development.

Florida’s springs and water table are also at risk from this massive surge in growth.

The Florida Office of Economic & Demographic Research says the statewide daily demand for water, 6.4 billion gallons as of 2015, is projected to increase by 17% in the next 20 years to more than 7.5 billion gallons as the population climbs to 25.2 million. That demand could be higher and the availability of that water lessened if climate change increases the frequency of droughts.

Not one of Florida’s five water management districts, which oversee permits for water supplies, “can meet its future demand solely with existing source capacity,” the agency stated.

A National Geographic feature on the issues surrounding water in the state showcased a 2018 study that showed a 32 percent reduction in average spring flows between 1950 and 2010; divers now walk through caves that they previously had to swim through. Research shows that a 10 to 20-foot drop in water levels can stop a spring flowing; some urbanized areas of Florida have recorded 90-foot drops. Silver Springs, one of the Floridan aquifer’s largest springs, has seen its output fall from 500 million gallons to around 200 million gallons per day—an alarming 60 percent decline. At the same time, half of all the water taken from the public water supply ends up watering private lawns, some 900 million gallons a day.

Traffic

When people ask the question “Is Florida full?” it would make sense that their first go-to is the traffic situation in many Florida cities.

This isn’t just perception, compared to the national average there are fewer miles of road per resident. A 2023 article by the Bradenton Herald highlighted that in a U.S. Census Bureau’s 2021 American Community Survey, HireAHelper researchers developed a composite score for small, mid and major metros to avoid if you hate commuting. Florida ranked as the worst state for commuters in the country, registering a 100.0 composite score.

When you look at lists that came out during the same year of the fastest-growing communities in the U.S., Florida had 15 out of the top 25. This wouldn’t contribute a massive amount of new automobiles to roadways if this was an even spread, however, these communities are often clustered along the same highway corridors.

The largest growth clusters occurred around the notoriously strained I-95 corridor on the central east coast, followed by The I-75 corridor on the southwest coast. This was tailed by Highway 589 and I-75 corridors north of Tampa between Ocala, The Villages and Crystal River.

Natural Disasters

An article by an NPR affiliate in South Florida highlighted some controversial policy decisions that happened in 2011 under former Governor Rick Scott. The state agency managing risky development in areas vulnerable to storm damage and more generally urban development patterns in Florida was dissolved. The results became evident after the destruction of Hurricane Ian in 2022.

“The result is what we’re looking at today,” said Richard Grosso, a land use attorney who worked for the state in the 1980s helping implement the 1985 law that created the agency, Florida’s Department of Community Affairs. “We put way too many people, way too much private and public investment dollars than we should have, in those vulnerable areas.”

In layman’s terms, the state used to manage where risky developments could be built. The risk comes from Florida’s regular severe weather conditions. Places like wetlands that could take the brunt of damage from flooding and many coastal areas were protected to stop the influx of cheap single-family developments from putting people in harm’s way. Since the decision to dissolve the agency, many of those areas have seen the most damage from storms over the years.

This lack of regulation also creates issues for emergency management officials. Creating maps of shifting floodplains, evacuation plans, communication plans and shelters takes time. When neighborhoods that didn’t previously exist are springing up faster than officials can prepare for storms, it puts many communities at an increased risk.

Social systems

One of the notable downstream effects of this largely unmanaged population influx is a strain on the various social systems within the state.

Even years after the COVID-19 pandemic, many hospitals across the state are facing overcrowding. Florida hospitals, on average, had about 77% of their beds occupied throughout 2022 due to a variety of challenges, said Mary Mayhew, president and CEO of the Florida Hospital Association in an article in the Miami Herald.

This video by News4Jax also demonstrates some of the issues with overcrowding in Florida hospitals, specifically in Emergency Rooms.

Schools across the state are also operating over capacity. In Volusia County, 14 schools are over 100% capacity as of 2023. St Johns County reported 10 schools over capacity, and Palm Beach County reported 18 schools over capacity, along with others in 2023.

As the prison population grows, federal auditors in 2023 said the state could face the risk of forced releases of inmates, lawsuits and even a federal takeover of its prisons. According to the audit, crumbling infrastructure, staffing shortages and a growing population are converging into critical challenges for the Florida Department of Corrections.

The answer

Someone who reads the above somewhat disheartening facts and figures may answer the question of “Is Florida full” with a simple and resounding yes. The real answer is if we stay within business as usual in our community development the answer will stay yes. The fact of the matter is that people want to live in the state, and without providing more housing for new residents they will continue to displace existing ones while driving up costs.

So how do we house more people while reducing the strain on all of these problems? We start building up instead of out. Devouring acres and acres of agricultural and ecologically stressed land is the only legal way to build housing in most of the state. A zoning map of most cities and unincorporated land will show that the vast majority of it is zoned exclusively for single-family residential housing.

This single-family zoning, alongside local regulations, will for the most part only permit subdivisions and cookie-cutter houses on a half-acre lot. Aside from strictly the amount of land this consumes with an exploding population, this style of development adds other stressors to existing infrastructure.

In most places in Florida, this results in places where the only transportation option is driving. With many of these new residents trying to commute to the same places as existing ones, this clogs up the highways and existing roads most of this development happens along. You can add more lanes, but as we continue to build new communities in the same way, those new lanes will quickly just fill up.

Maintenance costs on roads, water, power, telecommunications infrastructure, landscaping and more are increased when you have this mass scale of low-density housing as stretched out as it is in most of the state. On top of consuming more water, energy and concrete, there’s a reality that makes this style of construction unsustainable. Residents aren’t willing to pay the amount of taxes required to maintain this infrastructure, resulting in older waves of development falling into disrepair. When the infrastructure is maintained, it usually relies on state and federal subsidies.

In the more common scenario where maintenance is lacking, this puts many areas at further risk when it comes to fairly regular events such as heavy rain, flooding and wind in the state.

The unwillingness to pay for this scale of low-density infrastructure residents often results in underfunded and overcrowded public services and amenities in these areas. This is seen in the previously mentioned issues in schools, prisons and hospitals.

While many new residents desire this kind of lifestyle; the gated community, the private pool and the half-acre lot, mandating that it is the only kind of housing that can be built in the state is causing a myriad of problems from traffic to the environment. When we looked at the cost of living data, places that can no longer build new types of housing are also seeing a jump in the cost of renting and buying units.

Increasing the supply of all available units in existing urban areas would reduce the overall demand across the board, bringing costs down for everyone.

All things considered, building denser types of housing; apartments, triplexes, and duplexes, etc. in existing urban areas would increase the tax base while not raising taxes, reduce maintenance costs, consume fewer resources and provide housing to new residents without paving over new acres of natural and agricultural lands. An increased tax base and density could also accommodate public transportation services, which when done correctly can mitigate traffic from new residents that will move to Florida either way.

Retrofitting existing suburbs to allow for denser housing types as well as implementing mixed-use zoning, allowing shops and homes to be in closer proximity, would also better utilize already-developed land. Providing regular and high-quality public transportation could get more residents off the roads.

The other part of the solution would be to bring back the development authorities that existed in the 1980s and 1990s in the state. The ability to manage what areas pose too much of a risk for new housing in natural disasters could slow down the drastic climb in home insurance prices as well as preserve our natural lands.

Florida isn’t as full as it is just largely unregulated and chaotic land use. There isn’t an infinite amount of space, and our inability to properly manage our resources is what’s pushing the state’s carrying capacity into uncharted territory.

Patrice • Feb 13, 2024 at 6:04 pm

Changes are drastically needed to save the natural environment. We also need to do different in order to make living more affordable .

Lm • Feb 13, 2024 at 9:41 am

Tallahassee has a lot of areas that are Lot and block town houses Non-Condo Not necessarily duplexes, so one owner owns the unit. They were built mostly in the 80s, but I think it Contributes to housing being cheaper in Tallahassee than the rest of the state.